Isabella Ducrot; Elena Ferrante

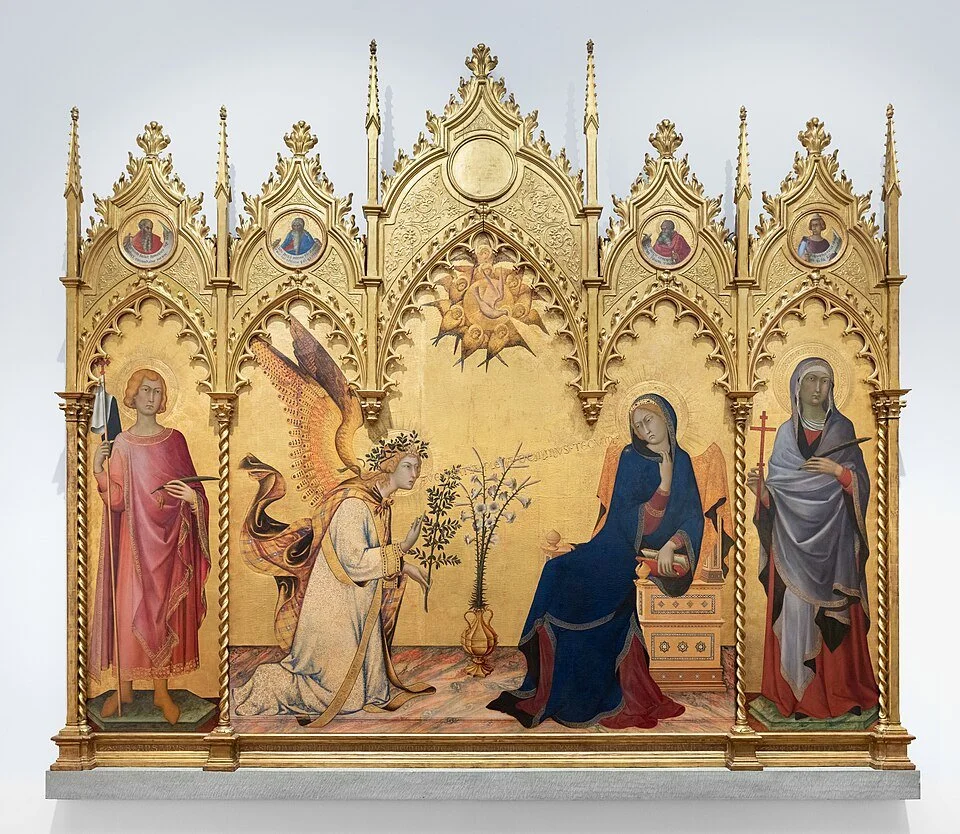

‘The Annunciation’by Simone Martini, c. 1333, the Ufizzi galleries, Florence

There are about two hundred and fifty pieces of fabric illustrated in Stoffe, the book on Isabella Ducrot’s collection of textiles, which are drawn from all over the world and date from the 9th century to recent times. Ducrot, Italian writer and artist, bought them in markets, from village stalls, in antique shops, and at auction, beguiled by their beauty and skills. Weaving cloth is one of humanity’s oldest crafts, she says, and fabric is often the first thing a newborn child experiences, besides the mother’s skin. Textiles, she adds, are not art in the conventional sense, because while a work of art demands personal creativity, fabrics are the products of a collective culture in which individuals efface themselves in the name of the group. Without this collaborative and social aspect, the textile is diminished.

In her book The Checkered Cloth, Ducrot describes the revelation she experienced after reflecting on the wonderful ‘Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus’ by the medieval Italian painter Simone Martini, which is housed in Florence’s Uffizi Galleries. The picture is luminous and the story is poignant, the Angel Gabriel telling the Virgin Mary of her future as the mother of Jesus, but what struck Ducrot most forcefully was the checked pattern of the cloth under the fold of the cape, visible just under the angel’s wings. She saw it as a humble, everyday fabric rarely seen in religious iconography, one normally worn by women or children, or used for utilitarian purposes. What could it mean, when worn by an angel? To Ducrot, the feminine connotations and simplicity suggested that it was ‘a fabric of connection’, greater than the sum of its parts. As she continued to think about it, Ducrot developed the idea that there is an enlivening ‘breath’ inherent in the fundamental structure of cloth; any fabric, stretched out and held taut, reveals myriad points of light at its heart.

Ducrot, born in Naples and living in Rome, is in her 90s and works every day in her studio. After decades of comfortable and agreeable obscurity, she has recently become surprisingly successful; ‘Can I say’, she has remarked, ‘that it makes me feel miraculous? I know us women are very in vogue right now, even more so when we are old, but, really, I had no expectations that all this would happen.’ At a time when anxiety and discord are so dominant in the world around us, Ducrot’s art, simple and deceptively naive, is startlingly life-affirming: warm, domestic, tactile, and intimate, it is also playful, frank, and earthy. Moving easily between abstraction and figuration, between the modest and monumental, her paintings, drawings, and collages depict lovers, landscapes, and objects, infusing them with bursts of colour and animating them with vibrant energy. According to the artist, her process is instinctive and free from rules. One of her most memorable exhibitions, ‘Il Miracoloso’, took place in December, 2021, at San Giuseppe delle Scalze, a baroque former church in Naples, for which Ducrot created a series of large works on paper, ‘The Annunciation’, ‘The Adoration of the Magi’, and ‘The Descent of the Holy Spirit’. The triptych created an intriguing tension between conventional religiosity, with which she grew up, and sensuous vitality. ‘Neapolitans live as if they were about to die’, she said.

A capacity to draw strength from frailty is a recurring theme in Ducrot’s work. In Women’s Life, another of her disarmingly agreeable and enlightening books, Isabella Ducrot writes about three core issues: childhood, what it is like to be a woman, and, perhaps most importantly, what she calls ‘ignorance’. The link between these topics is the experience of distance and alienation from what our culture has historically considered to be most significant or important, and Ducrot explores this from a personal perspective. Juxtaposing thoughts, short stories and autobiographical recollections, she shows not only how the ‘unknowing’ of childhood and the historical exclusion of women from many kinds of cultural or social discourse cause a sense of estrangement and suffering at being deprived of a ‘voice’, but how they also provide an opportunity to see life freshly and develop a way of expressing that vision. In old age, Ducrot says, ‘you can have courageous feelings and free gestures. As a woman, I have had a different story from that of men – I have suffered differently and rejoiced differently. ‘My story is about what I have not done. No university. No academies. No travelling. I began all that later.’

Ducrot’s journey from the restrictions of early life in Naples to her current sense of freedom has some interesting connections and contrasts with Elena Ferrante’s celebrated Neapolitan novels; they are similarly concerned with the development of female ‘voices’ and identity. Ducrot’s experience, perhaps due to a prosperous and self-confident upbringing, is predominantly benign and optimistic; the lives of Ferrante’s two protagonists, Lenù and Lila, both raised in a poor neighbourhood in Naples, are complex and conflicted. An article by Sara Farris suggests that one of Ferrante’s most intriguing concepts is that of ‘dissolving margins’, or smarginatura, which is how Lila describes the experience of her own body, as well as her perception of the people and objects that surround her. Their boundaries melt away or invert; as Farris puts it, the known becomes unknown, truth becomes falsehood, the beautiful becomes ugly, the familiar becomes unfamiliar and threatening. This ordeal is caused by Lila’s growing fear of a world that is changing in front of her, one that is shifting from traditional to modern values, with a consequent trivialisation of ideas, tastes, aspirations, and desires. While Lila at first seems to be the more ‘authentic’ and forceful character, Ferrante complicates the reader’s initial impressions. It is the socially mobile and self-doubting Lenù who tells us, with passionate honesty, about her struggles for authenticity; although, as a modern woman, she finds it difficult to live with firm convictions and consistent behaviour, she strives for the truth despite knowing that it is impossible to achieve. There is humanity in Ferrante’s writing, plenty of it, but there are none of the hints of transcendence that can be found in Isabella Ducrot’s texts.

A short article and film about Isabella Ducrot and her home: https://www.worldofinteriors.com/story/isabella-ducrot-rome-apartment

Isabella Ducrot’s exhibition at San Giuseppe delle Scalze, Naples: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=494Es-SyQK4&t=149s

On Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels: https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/there-is-no-true-life-if-not-in-the-false-one-on-elena-ferrantes-neapolitan-novels/

Image on index page: Isabella Ducrot, ‘L’Arte non è cosa nostra’, mixed media on Tibetan textile, 210 x 310 cms., courtesy the artist and Capitain Petzel

Exhibition by Isabella Ducrot at San Giuseppe delle Scalze, Naples, 2021