Tale of Tales; The Mouse & his Child

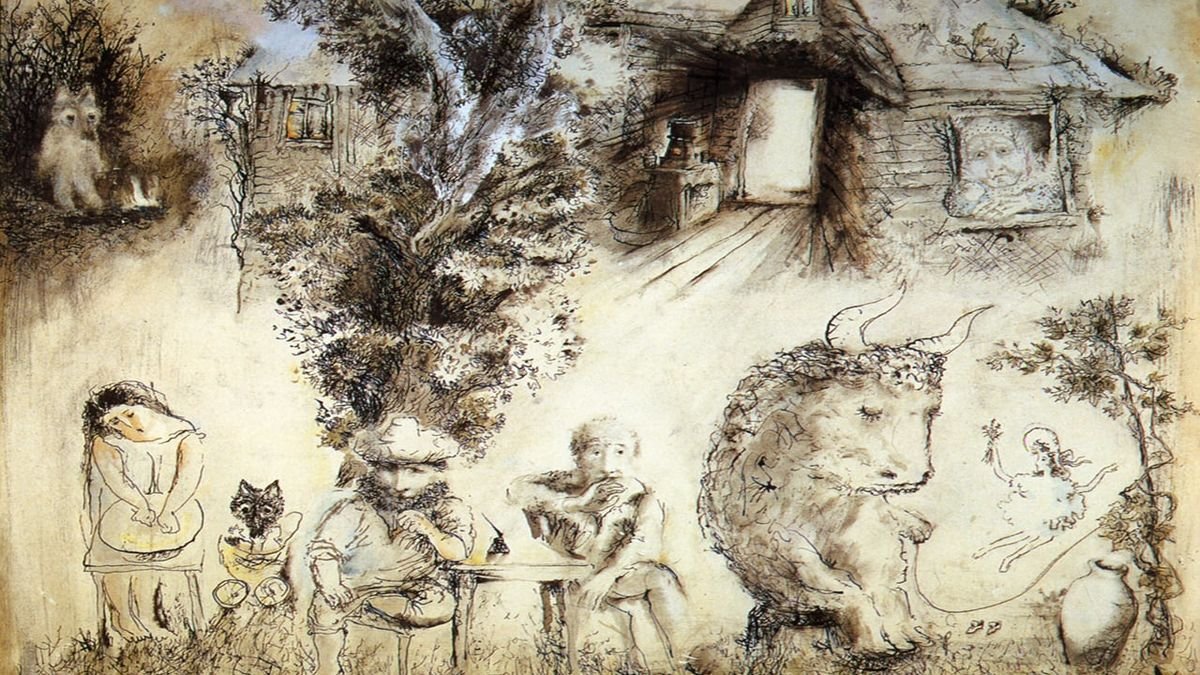

Artwork for ‘Tale of Tales’ by Yuri Norstein, with the wolf in the top left corner and in the foreground

In 19th century Russia, ways in which the wolf was perceived and understood were closely connected with national identity, and especially with a sense of how the country’s culture differed from that of Western Europe. The animal’s symbolism was contradictory; on the one hand the wolf was associated with strength, and thus with pride and self-esteem, but on the other, it also evoked backwardness and social disorder. It is unsurprising, then, that Russian hunters often relished the pursuit of wolves, and borzoi hounds, able to master and dominate them, were greatly admired. The possession of a wolf as a pet was a mark of distinction; it is said that Tsar Peter the Great owned seven of them, all pure white, and that they followed him around in his palaces.

‘Tale of Tales’, the celebrated Russian animated film made by Yuri Norstein in 1979, has a wolf as a protagonist, now transformed into a benevolent and somewhat whimsical creature. Poetically blending hopes and recollections, ‘Tale of Tales’ has been compared to Tarkovsky’s ‘Mirror’ because they both draw on memory and imagination; seemingly unrelated sequences are intuitively juxtaposed, one image or situation suggesting another, seldom rationally or predictably. The story is set in different worlds, expressed by varied forms of animation; the line between the imagined and the real is blurred and unsure. A baby, a little boy with crows and apples in the snow, a poet, a girl, a bull, dancers, and soldiers recur throughout the film; there are perhaps connections between them, but the overarching narrative, which may be tied to the life of the baby in the prologue, remains elusive. Dreamy, moody, and filled with melancholy, ‘Tale of Tales’ was inspired, according to Norstein, by recollections of his childhood; the wolf, for instance, derives from the lullaby that opens and infuses the film; his mother used to sing it to him.

When I watched it again recently, ‘Tale of Tales’ brought to mind a favourite book, The Mouse & His Child by Russell Hoban, beautifully illustrated by his wife Lillian and first published in 1967. Commonly considered to be a classic of children’s literature, it was introduced to me a long time ago by a good friend from university days, and I paid close attention to it after he named his home ‘The Last Visible Dog’ in homage to a key phrase and concept in the story, which tells of two clockwork mice, a father and son, who begin their lives in the warmth and security of a toy shop at Christmas time. They are carefree and content enough; when the key in the father's back is wound up, he dances in a circle, swinging his son up and down. The mouse child, however, wants another toy, the lady elephant, to be his mother, and the seal who balances a ball on her nose to be his sister; he’d like them all to live in the elegant doll’s house on the shop counter. He also wants to become self-winding. Unfortunately there is a long and arduous odyssey before these aspirations can be fulfilled; they are soon sold, and for several years they are only brought out at Christmas to dance under the tree.

On one of those festive nights, the mouse child is overcome with longing for the elephant and the doll’s house; breaking the ‘rules of clockwork’, he starts to cry. This alarms the family cat, who knocks down a vase onto the toy mice; smashed out of shape, they’re thrown into the rubbish bin, outside in the snow. A passing tramp, who has first seen them through the shop window, finds and repairs the toys, setting them on their way after telling them to ‘be tramps’. On they go, soon falling into the ruthless grip of Manny Rat, a shady, tyrannical villain who uses clockwork toys for slave labour and doesn't hesitate to crush the ones who get out of line. They escape and continue their search for the elephant, seal, and doll’s house, slowly gathering a motley family to help them fight for their lives and find a chance of happiness. Along the way they encounter the Muskrat, who promises to help them become self-winding, and discuss philosophy with the snapping turtle C. Serpentina, a thinker, scholar, and playwright who lives at the bottom of a pond; they also join up with a traveling theatre company called The Caws of Art, who are performing an experimental play called ‘The Last Visible Dog’, written by the same C. Serpentina.

The image on the label of Bonzo Dog Food cans - which eventually adorns a sign on the recovered doll’s house - shows a dog holding a can of dog food, on the label of which there is a smaller dog, holding a smaller can on which there is an even smaller dog, and so forth. In that light, ’The Last Visible Dog’ suggests patience, persistence, and infinity; the mouse and his child find that in order to realise their dreams they have to remain focused on a goal that is beyond all that the eye can see, while their journey is more challenging than they ever expected. The adventure comes to an end at yet another Christmas, when the tramp passes by again and peers into their world. He gazes at the house in all the brightness of its lights; he hears singing and merriment inside; he smiles and speaks to the mouse and his child for the second time. ‘Be happy’, he says.

The wolf in 19th century Russia: https://news.colgate.edu/researchmagazine/2018/12/excerpt-that-savage-gaze.html/

‘Tale of Tales’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w3sEoPYbNB4

A helpful article on Norstein and ‘Tale of Tales’: https://cometatomic.com/from-russia-with-folklore-the-intriguing-journey-of-tale-of-tales/

‘Mirror’ (full film): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NrMINC5xjMs

More on ‘The Mouse & his Child’: https://tygertale.com/2016/12/10/the-mouse-and-his-child-by-russell-hoban/

Image on index page: still from ‘Tale of Tales’

Current listening: https://aeolian.bandcamp.com/album/the-second-chamber

Image by Lillian Hoban for the cover of the first edition of The Mouse & his Child