Train Dreams

A still from ‘Train Dreams’

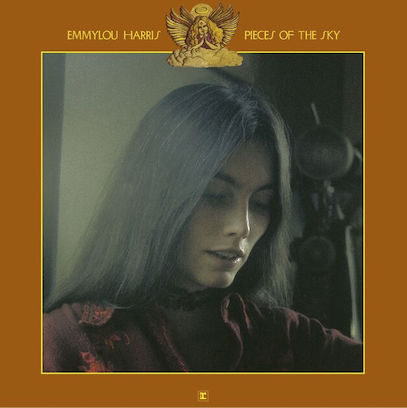

Emmylou Harris has been on a ‘farewell’ tour of Europe, and although I didn’t go to see her when she was in Dublin, I searched for the set list, which turned out to be full of old favourites. I listened to two of them again. The first was ‘Gulf Coast Highway’, a duet with Willie Nelson, written by Nanci Griffith and infused with the poignant sentimentality of so much country music; it tells of a couple reminiscing about their lives together, its characteristic moments of sadness lying in mournful thoughts about how they were forced to spend so much time apart because of the man’s job, which took him to distant places, and in the references to the black bird that will carry them to heaven after their deaths. The second, one of her most beautiful, was a song I first heard in 1975 on her album ‘Pieces of the Sky’, the grieving ‘From Boulder to Birmingham’, which eloquently and touchingly reflects Harris’ struggle to make sense of the world after the passing of her close friend, the musician Gram Parsons.

The words and mood of these songs unexpectedly brought to mind Clint Bentley’s sorrowful film ‘Train Dreams’, about a logger, an early 20th century itinerant worker who helped to clear woodland wildernesses, build bridges, and open the way for the American railroad. Robert Grainier, who grew up as an orphan, is at first stoically acceptant of loneliness and his tough job, but in due course he joyfully meets and marries a young woman with whom he has a baby daughter. Suffused with unexpected happiness, he becomes dejected at having to leave them for long periods in order to earn a living, and while often touched by the beauty of the nature that surrounds him, he is also troubled by the feeling that he is helping to despoil it. Suddenly his life takes an apocalyptic turn, from which he never fully recovers, except, perhaps, at the end of the film. There, as a much older man, he goes to town and happens to watch a television report from space; realising that travel has now moved from earth to sky, he decides to take a pleasure flight in an old biplane, and as it loops and turns, a stream of memories passes through his mind. We are told that Grainier died in 1968, alone and in his sleep, leaving no heirs and few traces of his existence, but on that spring day, ‘as he misplaced all sense of up and down, he felt, at last, connected to it all.’

‘Train Dreams’ is about a time when modern ways dramatically encroached on nature, altering its balance; it suggests, too, that the changes, which took place within a man’s lifetime, were probably inevitable, and that one of the mysteries of human life is how short it is and how it can be summed up in a fleeting sequence of remembered moments. Grainier, however, sensitively portrayed by Joel Edgerton, never loses hope, even when he founders in despair at how the world gave so much and then took it away from him. His deep sorrow is at least partly caused by the strength of his belief in love and family; it brings him immense pain, but also the strength and will to press onwards. Echoing the feelings in ‘Gulf Coast Highway’ and ‘From Boulder to Birmingham’, his ability to remember love as much as loss, and to be grateful for them both, is a kind of grace.

While the film’s themes - a quest for love and the celebration of unspoiled nature - have some similarities and connections with the lyrical cinema of Terence Malick, the book on which it is based, the short, gritty and hard-bitten novel of the same name by Denis Johnson, is strikingly different. In the original story, Grainier is crushed by a cruel and irrational world, eventually becoming a recluse living in the ruins of his family home, surrounded by the howls of mountain wolves and never quite abandoning the search for his lost daughter. The novel, highly lauded, tersely explores the sinister and unsettling world of the American frontier and the emotional collapse of a decent man. It also poses profound questions about the ultimate cost of the development of human society and civilisation.

Although in the novel every event and detail seem significant, contributing to a larger pattern of meaning, they don’t really do so, and at the end we are left with feelings of despondence and alienation. In contrast, while it is loyal to the book’s plot, the film quickly turns away from many of its most challenging elements, including the settler colonialism and racial violence that are inseparable from the country’s frontier history. Grainier is shown to have had some involvement in the killing of a Chinese worker, and the one Native American character, rather than living peacefully in the local village, as he does in the film, is cheated, bullied and attacked by white men before being symbolically killed by an oncoming train. Similarly, the novel does not allow the reader to find solace in Grainier’s final release from his tribulations, its refusal hinging on a peculiar event, present in both book and film, which involves his missing daughter. In the former, the utter strangeness of the incident defies any single interpretation and complicates the meaning of the story. The novel is tough and astringent; the film is sad but sweetly uplifting.

For further exploration:

Emmylou Harris and Willie Nelson, ‘Gulf Coast Highway’(1997): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8fEg3-mhy3E&list=RD8fEg3-mhy3E&start_radio=1

Emmylou Harris, ‘From Boulder to Birmingham’ (1975): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjLx7ESHRcA&list=RDJjLx7ESHRcA&start_radio=1

‘Train Dreams’ film review: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jan/27/train-dreams-review-joel-edgerton-drama

Review of Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/sep/13/train-dreams-denis-johnson-review